Hello and Welcome,

This is the April 2016 Climate

Update from Amalie Robert Estate.

April is a

cruel month. The vines are just waking up and starting to grow. They have about

six months until The Great Cluster Pluck and they are on a tear to “ripen their

seeds.” (This is vine code for “reproduce.”) The climate is transitioning from

the last of the particularly nasty winter weather including hail, of course,

and breaking bad into summer temperatures approaching 90 degrees – in APRIL!

Fortunately, we had some measurable precipitation, aka rain, to keep the vineyard

floor pliable enough to work in last year’s nitrogen fixing and soil holding fall

cover crops of barley and peas and to drill in the nitrogen fixing and moisture

sipping spring cover crop blend of buckwheat and vetch.

The vineyard

floor is where the real action is happening at Amalie Robert Estate in April.

We believe that the soil is the plant’s stomach and if you want to grow the

world’s best Pinot Noir, you need to tend to the vines’ appetite.

A primer for

nonfarmers: The air we breathe is made up of about 80% nitrogen. Some

plants (peas and vetch) are able to “fix” nitrogen out of the atmosphere and

make it available in the soil as a nutrient. Winter rains have a tendency to

wash away hillside topsoil if you do not use plants with fibrous roots (barley)

to help hold the soil in place. Our summers are typically dry and any spring

cover crops (buckwheat) have to survive mostly on the gift of morning dew. Shall

we proceed?

Nitrogen is a

macro nutrient, along with phosphorus and potassium. They are the three main

building blocks of all plant life. Phosphorous and potassium are “resident” in

the soil year round. These nutrients bind to the soil particles and hang on

through the winter rains. Nitrogen does not. And so the 45 inches of rain we

get every winter washes nitrogen out of the soil. That means each spring the

vines wake up to find there is very little nitrogen available to them. Unless

you planted a nitrogen fixing and soil holding fall cover crop the year before.

The view from

10,000 feet is to incorporate the nitrogen fixing and soil holding fall cover

crop of barley and peas into the moist spring soil to give the vines nutrients

for vintage 2016. And then to follow-on with the spring cover crop of nitrogen

fixing and soil sipping buckwheat and vetch to be incorporated into the soil just

after harvest to provide nutrients all winter long.

But wait, there

is more! The nitrogen fixing and soil holding fall cover crop of barley and peas

also gets drilled in just after harvest to complete the cycle for upcoming vintage

2017. In our previous lives, we would have called this an infinite loop where

the only way to stop it is to pull the plug. But this is agriculture, and not

just agriculture, but wine agriculture, aka viticulture, where if it looks

stupid, but it yields positive results, then it is not stupid.

The view from

ground level is a little more involved. There are several vineyard passes

required to make this happen and all of this work has to be completed before

the soil moisture in the top 6 to 10 inches of soil is gone for the year, as there

is typically very little rainfall after the end of April. Ernie has 3 tractors,

all Italians, and once you can get them started, they can affect significant

change. And that brings us to the implements:

First we have

the flail mower. It is accurate to say Ernie begins each growing season

flailing out in the vineyard. Every other row contains the nitrogen fixing and

soil holding fall cover crop that has grown all winter fixing nitrogen right

out of the air. The flail mower chops these plants into digestible pieces for

the soil.

Yes, it is

true. We are growing plants to feed our vines. The alternate approach is

applying chemical fertilizers. And when you see a vineyard that has permanent

grass in all the rows, it makes you wonder how they are feeding their vines.

Next on the

scene is the chisel plow. This is an old school implement whose purpose is to

open up and aerate our sedimentary soils and break up any compaction from the

tractor tires. Our soil type is Bellpine, a sandy clay loam. After years of

experience and countless rototiller tines, Ernie has discovered the rototiller

tines live much longer and more productive lives if he opens the soil with a

chisel plow first.

And speaking of

the rototiller, its main purpose is to lay down a beautiful seedbed for the nitrogen

fixing and soil sipping spring cover crop blend. The rototiller also helps seal

in the soil moisture. By fluffing the top 4 to 6 inches of soil, it breaks the

capillary action of water and prevents the transpiration of soil moisture from

the vineyard floor to the atmosphere.

Man that looks

nice!

The last pass,

and the one that you need to get done just before spring visits its last drizzle

of rain upon you, is drilling the water sipping and nitrogen fixing spring

cover crop of buckwheat and vetch.

The Schmeiser

seed drill is just about as a precision instrument as you will find in the

vineyard. Each drill consists of two disc blades to open a furrow and drop

seeds at a predetermined rate and then a follower wheel to press it down into the

moist soil. You know when that pass is complete as it looks like the rows have

been combed. And then Ernie does the rain dance out by block 2 and hopes for germination!

This bi-annual

process begins again in late September when the soil sipping and nitrogen

fixing spring cover crop is incorporated into the soil and the nitrogen fixing

and soil holding fall cover crop takes its place. While they look like dead

trunks sticking out of the ground, the vines’ roots are taking up nutrients all

winter long with the help of their little friends, the

Mycorrhiza.

The month of

May is the advanced class of canopy management. Getting those shoots to grow

straight up through the trellis is accomplished with hand labor, and a lot of

it. Ernie designed his trellis with three sets of moveable wires to catch the

explosive spring growth.

The goal here

is separation of the clusters to allow for good air circulation and sun

exposure that will allow hang time into the fall rains without risk of mildew

or bunch rot. If they start to rot before you want to harvest, you have to

accept the fact that they are not ripe, but with the rot they are only going to

get worse. That is why canopy management in May is oh, so important.

June brings us

Dena’s birthday bouquet in the form of a gazillion Pinot Noir flowers adorned

with bits of Chardonnay, Pinot Meunier, Syrah, Viognier and 24 vines worth of

Gewürztraminer. The vineyard is pungent with the heady scent of pollination. Add

105 days and that gives us an approximate harvest window. No more rain dancing

now until after harvest.

July is hedging

season. Ernie mounts the Collard hedger on the front of the tractor and takes

those unruly vines to task. Cold years require a tall canopy to maximize leaf

exposure to ripen our wine. Hot years, like the past two growing seasons, have

Ernie dialing down the leaf exposure to slow down sugar accumulation that gives

us more hang time into October to develop aroma and flavor on the vine. Early harvests,

and the resulting pre-mature fermentation, are typically the result of weak

canopy management discipline.

August is when

we start to see the little green berries start to blaze “en flagrante!” It is

also the time we estimate our crop load and start thinning excess clusters off

the vine. “Survivor: Vineyard Edition” so to speak… And of course, this also

includes the late to ripen wings. After all of this work, we don’t need unripe

flavors from the wings showing up in the wine because we cut corners. No sir,

that’s why our labels are square.

September is

the “hurry up and wait” phase of winegrowing, usually. The canopy has stopped

growing, the crop load is set, the nets are up and the bets are down. We know

the flocks of marauding birds, just like the rain, are due anytime now. Nothing

but risk as far as the eye can see. So we go to the top of our perfectly

positioned hill, take in the expanse of 60 to 70 tons of wine on the vine and

marvel in the gift Mother Nature has bestowed upon us.

It is going to

happen in October, you can count on it. Maybe we start in the first week or

maybe the week before and it goes right on through to November when we bring

the Syrah and Viognier home. The Great Cluster Pluck is the culmination of all

the decisions and weather events that shape the idiom of each vintage. And

while it is true that we harvest all of our fruit by hand, we go to great lengths

not to “bucket up.”

The numbers.

For those of you just joining us for the 2016 FLOGGING, this is the part of the

communiqué where we tell you what just happened, with perfect accuracy, whether

you knew it or not.

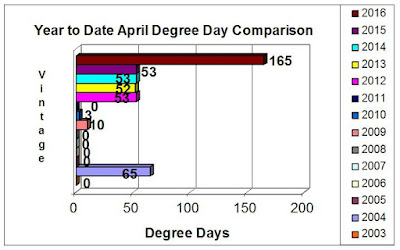

Degree days,

aka heat accumulation, is the way that humans try and understand what the vines

are experiencing during the growing season. A growing season at Amalie Robert

Estate in the Willamette

Valley with around 2,000

degree days is a pretty moderate vintage. Below that mark we typically see wines

defined by elegance and brilliant acidity. Above 2,000 degree days we see more

expansive wines of great depth and character. And in Oregon we vacillate to both ends of these

extremes frequently. This is nice as it gives people the opportunity to discuss

the ying and yang of each uniquely Oregon

vintage. Something for everyone, you could say.

We come up with

these numbers by taking a temperature reading in the vineyard every 12 minutes.

At the end of the period, we average those readings and deduct 50 degrees,

because below 50 degrees it is too cold for the vine to get much done. We then

multiply the average by the number of days in the period. That results in the

degree days for that period, typically one month at a time. We accumulate those

degree days from April 1st through harvest, or October 30th,

whichever comes first. Next month we will explain tractor gearing vis-à-vis

ground speed as measured in furlongs per fortnight. This graph depicts the

historical degree days specific to Amalie Robert Estate. Note: your mileage may

vary:

For the month

of April, we accumulated 165 degree days. The high temperature was 88.9 degrees

on April 19th and the low temperature was 37.8 degrees on April 4th. Once again we see a warm start to the growing

season, but at this point on the calendar anything could happen, and most

likely will.

We will be

keeping a keen eye on nighttime temperatures again this year. The 2014 and 2015

vintages saw elevated nighttime temperatures and that was the catalyst that brought

early ripening as defined by sugar accumulation. Sugar accumulation is

typically a response to heat in the vineyard – the warmer it is, the faster the

berries accumulate sugar.

Warm nighttime

temperatures are sneaky because the daytime temperatures may not be that hot,

but the vines continue ripening the fruit all night long because it is (well)

above 50 degrees. And this is relevant because once the berries accumulate 25

brix worth of sugar (15% alcohol), you gotta pick them otherwise the yeast will

die before completing fermentation leaving you with a “stickie” Pinot Noir.

Rainfall was

perfectly timed to germinate the cover crop with a total of 1.57 inches for the

month of April providing a year to date total of 24.34 inches. The year to date

number is important because we are dry farmers. We believe the irrigation

program is far too important to leave to modern man, so we trust Mother Nature

to get it right. However, we always like to start the growing season with the

soil fully charged with water.

Please consider

joining us at the winery for our Pre-Memorial Day weekend. This event is open

to our e-mail list only and is not otherwise publicized. We will be showing,

among other things, some of Ernie’s Unicorn wines. Dena will be sending out the

details shortly. Not to be missed…

Kindest Regards,

Dena & Ernie

No comments:

Post a Comment